To watch me deliver the full lecture and view the presentation, click here.

I recently gave a lecture about COVID-19 and vaccination with specific information for patients with IBD. This lecture was recorded on July 21st, before the CDC issued updates to their masking recommendations. However, the explanation of pressing and new developments in the pandemic remain on point.

The Current State of the Pandemic: Vaccines and Variants

To date, July 30th, 2021, nearly 35 million Americans have been infected by SARS-CoV-2 and 610,000 Americans have died from COVID-19. Despite these sobering numbers, the United States has made significant progress towards eliminating the threat of COVID-19. Almost 164 million Americans are vaccinated, which accounts for 57.7% of those 12 years of age and older and 49.4% of the total population of the United States.

Vaccination rates in rural communities remain lower than metropolitan areas and the death rate from COVID-19 in non-metropolitan areas has exceeded that of metropolitan areas since December 2020. Communities with low vaccination rates face a heightened risk of outbreaks from new virus variants.

The word variant has come to the front of discourse surrounding the pandemic and it is important to clarify this term. A variant consists of a mutation in the virus, which can either be lethal to the virus, meaning it loses functionality because of the mutation and dies, or it mutates and gains a survival advantage over its predecessors. When mutations produce a variant with advantageous traits, the resulting virus is often more contagious.

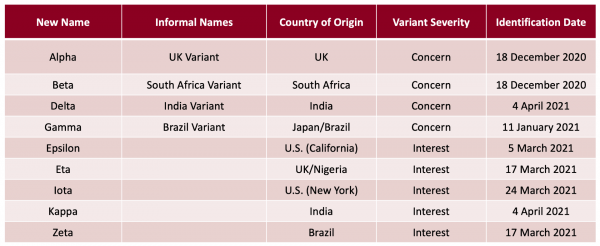

Health organizations categorize variants into three groups: variants of interest, variants of concern, or variants of high consequence. These categories correspond to increasing infectiousness and disease effects. Variants of interest may cause an increase in cases or a cluster of cases and have limited spread. Several SARS-CoV-2 variants of interest have been identified, as seen in the table below. Variants of concern increase the spread of the disease and may increase the disease severity. The Alpha and Delta variants—formerly referred to as the UK and India variants—fall into the variant of concern category. Currently, health leaders have not identified any SARS-CoV-2 variants of high consequence.

CDC. “SARS-CoV-2 Variant Classifications and Definitions.” Accessed 20 July 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/variant-info.html.

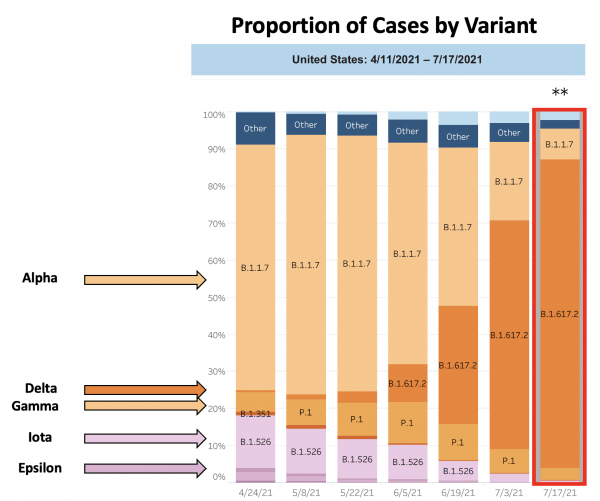

While media headlines have done a great job bringing Delta into our everyday vocabulary, whether or not Delta poses a legitimate threat at this stage in the pandemic may be less evident. Over the past month, Delta has emerged as the most prominent variant in the United States. The stacked bar chart provided by the CDC below identifies the proportion of variants among identified cases of COVID-19. This chart shows that Delta went from less than 1% of all COVID-19 cases in late April to 83.2% of cases on July 17th, indicating that the mutations in the Delta variant make it more infectious than other variants.

CDC. Variant Proportions. Accessed 20 July 2021. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#variant-proportions.

While more data are collected every day, scientists are primarily concerned with Delta’s increased infectiousness. In comparison with the original strains of SARS-CoV-2 where on average an infected individual infected 2-3 others, those infected with Delta infect approximately 6-7 other people.

Vaccination continues to be the strongest protection against COVID-19, including Delta. Currently available vaccines—Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, and Johnson & Johnson—effectively protect against the Delta variant. All three companies have submitted data to the FDA and CDC demonstrating their efficacy against Delta. These vaccines function by producing antibodies that identify SARS-CoV-2 via its spike protein, which remains an effective target against Delta.

COVID-19 in People with IBD

After all the talk about variants and contagion, let’s move on to some good news. People with IBD do not have an increased risk of getting SARS-CoV-2 infection. Additionally, people with IBD who contract COVID-19 do not have different disease outcomes than the general population.

In regards to IBD medication, initial studies show that there is no increased risk of severe COVID-19 infection in patients on aminosalicylates, biologics, or immunomodulators. However, steroids were associated with worse COVID-19 outcomes. While it is under investigation, there are currently no data on long haul symptoms or problems in IBD.

To better understand COVID-19 outcomes in patients with IBD, several national and international organizations have come together to create the SECURE-IBD database, a registry for documenting COVID-19 outcomes in patients with IBD. This database has resulted in many findings, specific to IBD treatments and their impact on COVID-19 outcomes.

In a June 28th update, SECURE-IBD reported that corticosteroids are associated with increased risk of severe COVID-19, biologic therapy is associated with decreased risk of severe COVID-19, and there is no significant association with 5-ASAs and severe COVID-19.

Several other studies of COVID-19 and IBD are ongoing, including PREVENT COVID, CORALE, and ICARUS IBD.

Media reports about immunocompromised populations and vaccine efficacy conflate, confound, and confuse patient populations on immunoregulatory therapies. The media’s most prominent error originated from findings that organ transplant recipients have a reduced antibody response from the vaccine compared to the general population. Media reports misrepresented this finding by attributing poor vaccine efficacy to all immune mediated conditions.

The specific mechanisms and cellular pathways targeted by IBD therapies are distinct from those of people in an immunocompromised state caused by different diseases or procedures. As shown by the data, vaccines are effective in patients with IBD whether or not they are on therapy. International guidelines recommend that all patients with IBD should receive a COVID-19 vaccine.