By David T. Rubin, MD, Professor of Medicine, University of Chicago Medicine

As testing for SARS-CoV-2 is expanded and serologic antibody testing becomes available, we are faced with a number of different clinical scenarios. I have outlined the different situations below, along with the considerations related to restarting medical therapy for the IBD.

Possible outcomes of patients infected by SARS-CoV-21:

- remained asymptomatic and have mounted immunity to the virus,

- cleared the virus in some other way but without sustained immunity (unclear but possible)

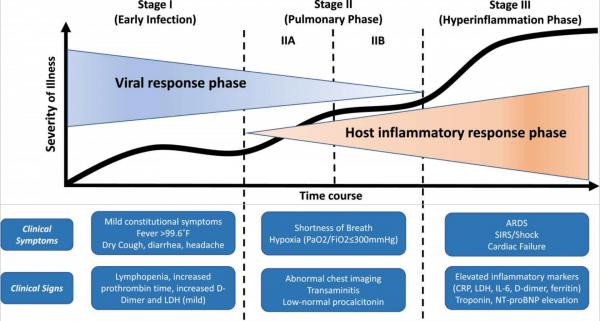

- developed COVID-19 (defined as symptoms, fever, radiographic abnormalities on imaging of the chest, lymphocytosis or lymphopenia, etc.2) and recovered completely either in the community or after hospitalization, or

- died from the COVID-19 complications usually of respiratory failure complicated by secondary infections and multi-organ failure.

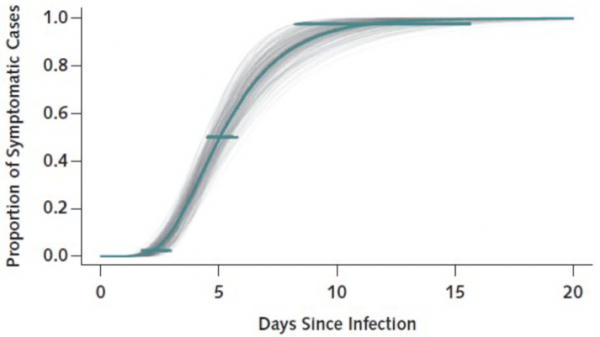

- As we currently understand it, those people infected with SARS-CoV-2 who develop COVID-19 (symptoms, fever, radiographic abnormalities on imaging of the chest, lymphocytosis or lymphopenia, etc.2) appear to do so within 2 weeks.3 The recommendations to monitor patients for two weeks comes from this understanding. In those two weeks, it should be clear whether ongoing delay or holding of existing IBD meds is needed. It is correct to wonder about delayed disease onset in patients who are infected, but this appears to be unlikely.

- We do not see a spike of patients on our immune therapies for IBD (and for that matter neither do our rheumatology colleagues in their patients) and disease presentation or worse outcomes. Therefore, while this is weak evidence, it certainly seems likely that many patients with IBD have been infected while on their therapies and recovered without knowing it or with minimal symptoms. This is good news. (I certainly agree that the absence of a thing doesn’t mean that it can’t or doesn’t exist.)

- The availability and validation of serologic testing will clarify some of this. We will hopefully know sooner than later that SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies confer immunity and reassure us in this regard.4 So, we won’t be looking for persistent virus in our patients but rather immunity.

As for when to restart therapy in patients who got sick with COVID-19, this is an active area of discussion. In both the IOIBD document5 and the AGA piece6, we tried to address this but without good evidence (yet).

Here are the considerations and options:

- Asymptomatic for 72 hours. (is this too soon?)

- Asymptomatic for 14 days. (is this too long?)

- RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 in nasopharynx negative twice, at least 48 hours apart. This is cumbersome for outpatients, and we don’t know the negative predictive value of two negative tests, but in an asymptomatic patient it seems that it would be high.

- Development of convalescent antibody IgG titers to SARS-CoV-2 with or without resolution of IgM antibodies. This may persist and take a long time, so is probably not needed in order to restart therapy.

- Something else…. (stool PCR? probably not needed)

Until we have effective and validated vaccines, this is where we are in my opinion. And then, of course, we will want to know how to vaccinate our patients with IBD who are on immune therapies. Will the vaccine confer immunity as effectively in these patients or will we need to confirm so with subsequent titers? (I think likely)

Thoughts and comments are welcome.

David T. Rubin, MD

Professor of Medicine, University of Chicago Medicine

References:

- Siddiqi HK, Mehra MR. COVID-19 Illness in Native and Immunosuppressed States: A Clinical-Therapeutic Staging Proposal. J Heart Lung Transplant. March 2020:Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2020.03.012

- Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus–Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061-1069. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.1585

- Lauer SA, Grantz KH, Bi Q, et al. The Incubation Period of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) From Publicly Reported Confirmed Cases: Estimation and Application. Ann Intern Med. March 2020:Epub ahead of print. doi:10.7326/M20-0504

- Woo PCY, Lau SKP, Wong BHL, et al. Longitudinal Profile of Immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgM, and IgA Antibodies against the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) Coronavirus Nucleocapsid Protein in Patients with Pneumonia Due to the SARS Coronavirus. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2004;11(4):665-668. doi:10.1128/CDLI.11.4.665-668.2004

- Rubin DT, Abreu MT, Rai V, Siegel CA, International Organization for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Management of Patients with Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results of an International Meeting. Gastroenterology. April 2020:Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.002

- Rubin DT, Feuerstein JD, Wang AY, Cohen RD. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Expert Commentary. Gastroenterology. April 2020:In press. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.012